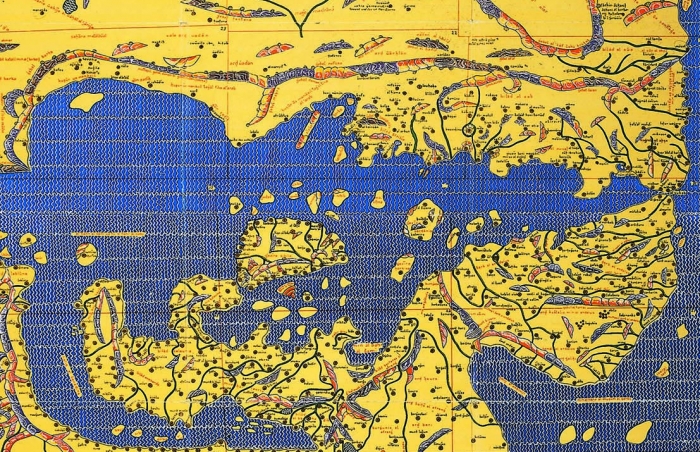

Šeriš, Jerez, Sherry: A place on the map

The Šeriš of al-Idrisi in Al Andalus

As Manuel María González Gordon relates, in 1967, after months of dispute in the London courts against the producers of so-called “British Sherry”, the Consejo Regulador and the Sherry producers managed to get them to drop the fraudulent use of this name from their products which constituted unfair competition to genuine Sherry.

74 witnesses were called in a case which lasted 29 days, during which numerous pieces of evidence were produced: hundreds of bottles of wine, 1,600 labels, over 3,000 price lists, hundreds of advertisements… Defending the interests of Sherry were the president of the Consejo Regulador, Salvador Ruiz-Berdejo, José Ignacio Domecq, Manuel María González Gordon (who, because of his advanced age was interviewed in Jerez) and Jaime Oliver Asín.

In support of their argument copies of valuable documents held in the British Museum were presented, such as an English comedy from the XVII century and diplomatic letters between Queen Elizabeth I and her ambassador to the court of Spain. Along with these was the real “ace up the sleeve”, the item which really determined the outcome of the case, which was the copy of a fragment of a XII century map in which could be clearly read the name of “Šeriš”.

An arabist in the Sherry Case

Now came the turn of one of the key witnesses for the Sherry producers: the philologist, historian and researcher, Jaime Oliver Asín, nephew of the distinguished arabist Miguel Asín Palacios, who produced as evidence the copy of the map drawn by the Arab cartographer al-Idrisi conserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford with consummate care by the German researcher Konrad Müller in 1926.

Oliver Asín, in his testimony to the court and with the map as proof, was able to demonstrate that the Arabic place name “Šeriš” was already in use in the XII century in reference to Jerez, and that the English word “Sherry” was not derived from Jerez, rather that both words were derived from the Arabic name “Šeriš”. Thus, while in Spain the word evolved via Xeres to Jerez, in England it evolved via “Sherris” to “Sherry”.

The al-Idrisi map, upon which arabist Oliver Asín based his historical and philological argument, was thus the key piece of evidence in what came to be known as the “first Sherry case” and which opened the way for the prohibition of the unauthorised use of the word “Sherry” for any wine not produced in Jerez.

But the story of this curious map began, as we shall see, in Palermo eight centuries ago.

The al-Idrisi map

During the first third of the XII century, Roger II of Sicily had unified the territories seized by the Normans from the Arabs in the south of Italy and formed a kingdom. Conscious of the importance of naval power to maintain the unity of his possessions and his strategic position in the Mediterranean, he created in Sicily a school of navigation for which he recruited the most renowned Jewish and Arab geographers and cartographers.

Thus it was that at the king’s invitation, the Ceuta-born Ibn Idris Ash-Sharif, better known as al Idrisi and the most famous geographer of the time, moved to the court of Palermo towards 1138. Roger gave al Idrisi, who had been trained at Córdoba in Al Andalus, the job of producing a description of all known land which should be based on direct observation rather than a recompilation of works already written.

To do this, al Idrisi spent the next 15 years visiting the countries and cities of the Mediterranean world and compiled all the valuable information he obtained into a great work which first saw the light of day in 1154 entitled “The Book of Roger, a Diversion for Whom Wishes to Go Round the World” (Kitab Ruyar). Included with it was his greatest contribution and what would make him famous for many centuries to come: his “Universal Map” also known as “Tabula Rogeriana”, in the making of which he followed the geographical thinking of Ptolemy. As professor Bustamante Costa says, the texts of al Idrisi are: “a description of the countryside, centres of population, crops and distances, it adds information to the planisphere including facts obtained from the most diverse sources from books or word of mouth, often exact and sometimes, inevitably, fanciful.”

The works of al Idris were very successful in his day and on throughout the centuries, being quoted, copied and reproduced with additions and subtractions to his texts and maps on numerous occasions. It was also translated into various languages and was printed for the first time in Europe, in Arabic lettering, in Rome in 1592. In 1619 it was partially translated into Latin and published. Anyone who looks at his maps should be reminded that, like all Arab maps of the time, north and south are inverted.

Šeriš in the works of al Idrisi

Noteworthy among the oldest copies of his work to have survived are that in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris from the year 1300 which is missing a fragment of the south of the Iberian peninsula, and that dated 1456 from Cairo which is conserved at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

The German researcher Konrad Müller, who was able to study the original copies, published an interpretation and adaption of the Book of Roger and the Tabula Rogeriana in 1926 based on the documents at Oxford. The Oxford fragment of al Idrisi’s Mapamundi published by Müller which corresponds to the south of Al Andalus was that used as proof in the First Sherry Case since it shows in all clarity that “Šeriš” in Al Andalus is in fact Jerez. The map shows neighbouring towns such as “Isibilia” (Sevilla), “Kadis” (Cádiz), “Almarin” (Medina), “Tarif” (Tarifa), “Algezira” (Algeciras), and a little further away are “Osuna” (Osuna), “Asiha” (Écija), “Arsiduna” (Archidona) and “Malaka” (Málaga).

As well as the presence of Šeriš in the maps in the Tabula Rogerina there exist other mentions of Jerez in the texts of the Book of Roger such as a geographical description. Al Idrisi mentions over 250 villages and towns in the Iberian Peninsula of Al Andalus. He offers interesting descriptions of the ones near Jerez such as Sanlúcar, Cádiz, Rota, Medina Sidonia, Arcos, Paterna and Morón based not only on his own observations but also those of other travellers, and especially the writings of al-Razi the great X century chronicler of Córdoba who was the author of the fullest geographical description of Al Andalus: “General Chronicle of Spain by the Moor Rasis”. So more than including Šeriš in his map, al Idrisi includes in his text a brief but interesting description of Jerez, its position in relation to other towns, its surroundings and its products:

“From Carmona to Xerez, a town in the province of Sidonia, 3 days.

From Sevilla toXerez, two long days

Xerez is a fortified town, of medium size, hemmed in by city walls, its surroundings have an agreeable aspect because it is surrounded by vineyards, olive groves and fig trees. The land also produces wheat and subsistence items have a reasonable price. From Xerez to the island of Cádiz, 12miles,that is from Xerez to Alcanâtir (the bridges), 6 miles, and from there to Cádiz, 6 miles.”

In some Arab maps prior to that of al Idrisi there are references to the geographical position of Jerez, for example the Magreb Map by the Persian Al-Istajri of 934 which shows the town of “Šiduna” on what is now the site of the castle of Doña Blanca. The map of the Iraqui geographer Ibn Hawqal of 950, one consulted by al Idrisi, does not show “Šiduna” but does mention “Šeriš Šiduna” or Jerez.

Despite everything we feel a special fondness for al Isidri’s work produced a century later since he not only helped win the First Sherry Case but also gave our Šeriš or Jerez for evermore “a place on the map”.

Author: José y Agustín García Lázaro, Originally published in Diario de Jerez 6.3.2016

10 March 2016